A new militant mood came to life in the autumn of 1889 in Bristol. That year the Gas workers branches of London and Bristol amalgamated. On 9th October they went on strike in support of a wage improvement. The company hired 120 scabs from Exeter but despite police escort failed to get them through the picket-lines. The employer agreed to the union demands.

The Bristol Trades Council organised a celebration attended by around 10,000 people. 2,000 dock workers went on strike for more pay and after that struck again for a closed-shop. With the support of the gas workers and others, women cotton workers in Barton Hill Mill went on strike for better pay and conditions. On 26th October a huge procession through Bristol of some 15,000 people was addressed by Ben Tillett. On the Strike Committee were Helena Born and Miriam Daniell from the Marxist Bristol Socialist Society founded in 1885.Helena Born was born in Devon in 1860 and attended Hatherleigh School in Taunton. She loved music, and when the family moved to Bristol she sang in the choir of Oakfield Road Unitarian Church. An artist and poet friend was Miriam Daniell, whose studies had led her to embrace socialism. Both had similar tastes. They explored nature in the course of long rambles and Miriam shared her enthusiasm for humanitarian causes. They reflected links between the working class and middle class intellectuals but also between industrial and political ideas.

Helena and Miriam threw themselves into the work of the strike organising committee. They addressed meetings, led parades, collected strike funds and distribute relief. They gave up their comfortable quarters in Clifton to live in Louisa Street, St Phillips, a house that became a hive of socialist activity.

The month-long Barton Hill strike attracted massive public support. The women settled after some modest concessions from the employer who had threatened to close down the works if the strike continued. Miriam Daniell wrote a pamphlet on why equality between the sexes must be the hallmark of new unionism. Miriam and her lover, Robert Allan Nichol, wrote The truth about chocolate factories or modern slavery, its cause and cure. Nichol was named as correspondent in the divorce in 1893 and after she became pregnant the couple emigrated to Boston, America. The child, Eleanor, was called ‘Sunrise’. They were involved with the radical Boston Liberty Circle but Miriam died suddenly in 1901 in San Francisco.

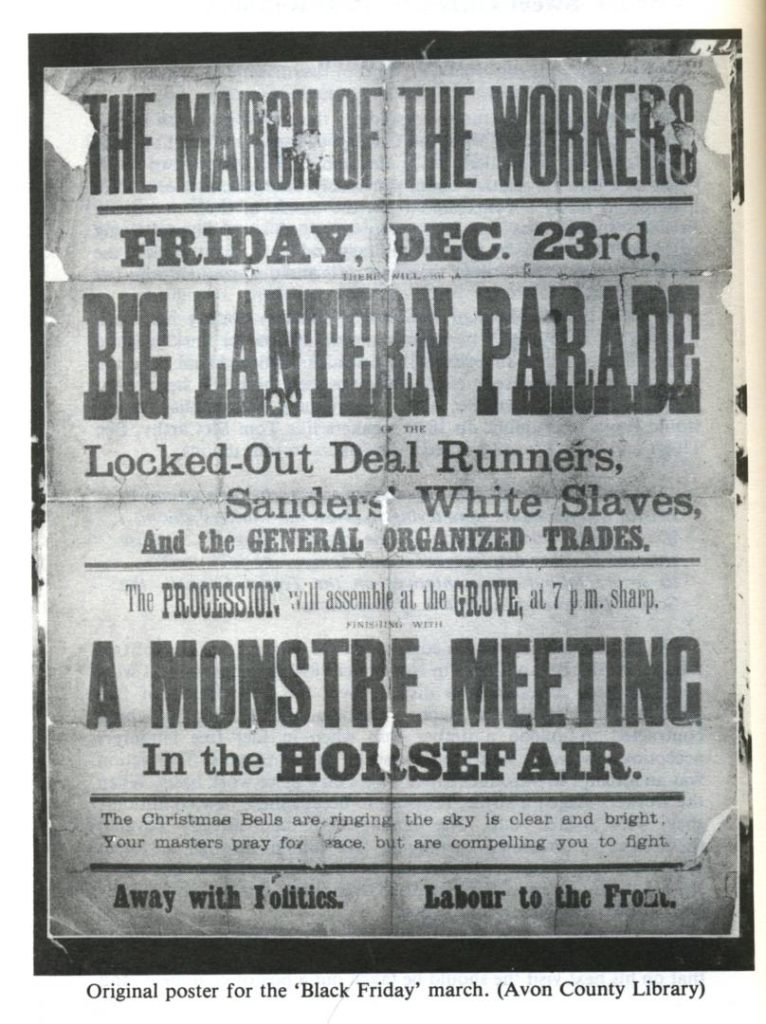

Sander’s White Slaves

Enid Stacey (1868-1903) was a young middle class socialist active in the city of Bristol. Her father, Henry Stacey was an artist and one of the leading socialists in the area. He painted the No.1 branch of Bristol Gasworkers’ banner. Enid became honorary secretary of the Association for the Promotion of Trade Unionism among Women. When her participation in strikes resulted in clashes with police she got fired from her job as a tutor.

Enid Stacey (1868-1903) was a young middle class socialist active in the city of Bristol. Her father, Henry Stacey was an artist and one of the leading socialists in the area. He painted the No.1 branch of Bristol Gasworkers’ banner. Enid became honorary secretary of the Association for the Promotion of Trade Unionism among Women. When her participation in strikes resulted in clashes with police she got fired from her job as a tutor.

When the women at Sanders Sweet Factory, Redcliffe Street, came to Enid for help in 1892 she told them to join the Gasworkers’ Union. The 300 women workers worked excessive hours, suffered large fines and were locked in the factory during dinner breaks! They revolted when the employer extended their hours of work by an hour-a-day and abolished their 15-minute meal-break! The nickname ‘Sander’s White Slaves’ was well earned!

Check out the banners gallery here.

Bristol Strikes

Sarah Edwards, one of the women who had first talked to Enid, was dismissed. All of her workmates walked out! The strike began in early October 1892. The women went around Bristol every day with collecting boxes. Gas workers and dockers regularly marched with the women. In the same month, the dockers were locked out by the employers anxious to smash the Dockers’ Union. Regular processions all added to a sense of crisis in the city. From the start the police hounded the women and pickets. Following complaints in the press about begging, magistrates and police became increasingly hostile. On 18th December 1892 the authorities banned an evening torch-light parade. The women accepted the ban and instead collected funds in the Horsefair. During the evening the police and militia charged them with batons, swords and lances! Miraculously no-one was killed although many were injured.

Black Friday

On Friday 23rd December 1892 another huge demonstration was organised. It was to be a peaceful lantern parade to collect money for the strikers and locked-out workers. The organisers agreed to police requests to ban the penny ‘Chinese’ lanterns but there was no agreement on the route. Some 200 mounted troops tried to restrict and split the march. At Bristol Bridge there was a confrontation during which several people were hurt. A meeting of members of the Liberal Reform Club, Brunswick Square, which was held that same evening, passed a resolution that appeared in the press next morning. It condemned: “the dastardly conduct of the authorities for instructing the military and police to charge the peaceful and orderly meeting of citizens held in the Horsefair this evening.”

On Friday 23rd December 1892 another huge demonstration was organised. It was to be a peaceful lantern parade to collect money for the strikers and locked-out workers. The organisers agreed to police requests to ban the penny ‘Chinese’ lanterns but there was no agreement on the route. Some 200 mounted troops tried to restrict and split the march. At Bristol Bridge there was a confrontation during which several people were hurt. A meeting of members of the Liberal Reform Club, Brunswick Square, which was held that same evening, passed a resolution that appeared in the press next morning. It condemned: “the dastardly conduct of the authorities for instructing the military and police to charge the peaceful and orderly meeting of citizens held in the Horsefair this evening.”

Bristol Bridge

Ben Tillett was arrested for ‘inciting crowds to riot’. The trial that followed saw protests involving up to 30,000 people. The case was moved to London where he was acquitted. In January 1893 the Sanders’ strikers and the dockers joined forces and in drizzling rain five or six thousand paraded through the city to the Grove where two mass meetings were held.

A great demonstration was organised for Saturday 9th February 1893. The procession took a long route: West Street, Stapleton Road, Seymour Road, Newfoundland Road, Union Street, Bridge Street, Baldwin Street, and the Quay to the Grove. The marchers walked up to twelve abreast and the procession about a mile-and-a-half long. Fifteen bands of music were in attendance, and a wealth of banners displayed.

Support for the strikers grew and financial aid rose dramatically. Strike pay was now higher than the actual wages paid by Sanders! The strike lasted until mid-1893. The employer conceded improvements in terms and conditions and the strikers returned to work. All of the sacked activists were placed in new jobs. The strike was hailed a success. During the strike a total of 25 women were arrested and taken to court. In every case the union successfully defended them.

After the dispute Enid Stacey became active in the formation of the Independent Labour Party, becoming a travelling speaker for them in 1895. She spoke and wrote of her vision for socialism and women’s rights. Enid died from an embolism aged just 35.

For more check out pamplets from the Bristol Radical History Society:

- The Bristol Strike Wave of 1889-1890 – Socialists, New Unionists and New Women

- The Origins and an Account of Black Friday – 23rd December 1892

- The Maltreated and the Malcontents – Working in the Great Western Cotton Factory 1838-1914

- Turbulence – Labour and Gender Relations in Bristol’s Aircraft Industry during the First World War

- Bristol and the Labour Unrest of 1910-14