The outbreak of the war in 1914 led to patriotic fervour. The massive government campaign to recruit volunteers led millions of people of fighting age to sign up. Those who opposed the war were overwhelmed by the government’s call to arms.

Enlistment in 1915 at St Austell, Cornwall, photo: China Clay History Society

Radical voices were all but drowned out in the jingoism. Kier Hardie argued that British workers had more in common with their German counterparts than British generals. He clung to the threat to call a general strike if war was declared. Ernie Bevin was in Bristol during the first weekend of the war. At a mass meeting he called for international action to stop the conflict. But trade union leaders, suffragettes and Labour politicians could not defy the popular mood. Ramsay MacDonald, a pacifist, resigned as leader of the Labour Party. Campaigns for voting reform and industrial action were set aside. An embargo was declared on all claims and disputes.

The eagerness to enlist was not shared by all. Rural areas tended to be slower to provide volunteers – Cornwall had the lowest recruitment rate in the country in the first year of the war. Some of this was explained by the need to maintain agricultural production. It was hardly surprising that farm workers didn’t rush to join-up when the farmer didn’t want sons to sign up. Politicised by their strike in 1913, some Cornish clay workers were reluctant to sign up to fight. The socialist preacher, the Reverend Booth-Coventry who had been such a supporter of the strikers, was reported to have been jeered when he appealed for workers to enlist. Less than three per cent of Cornish men enlisted by November 1914 compared to around ten per cent nationally. In the Forest of Dean only 600 out of 7,000 miners signed up and opposition grew to the ‘combing out’ of miners to fight.

Some unions and trades councils came out against the call-up, especially at the start of the war.

In June 1915, Bristol and Plymouth Trades Councils passed resolutions against conscription. The half-yearly report of Plymouth Trades Council in January 1915 said: “Circumstances over which the millions of workers in Europe had no control whatever have involved them in all the horrors of a ghastly war. None of the workers will be one penny the richer or one bit the happier for the sacrifices they are called upon to make or the suffering they will have to endure. We find ourselves plunged into catastrophe without our knowledge or consent.”

As the horrors of the conflict became apparent, the flow of volunteers slowed and the government moved towards conscription to fill the ranks and replace those being slaughtered in the trenches.

War at home

Munitions workers in Poole

The need to provide the arms, munitions, food and supplies meant that all available labour was needed. 5.6 million workers were enlisted to fight. Labour restrictions were lifted to allow women and unqualified workers to work. Unions like the Workers’ Union and the Transport Workers’ Federation set about to recruit the new workforce.

In 1917 the Great Western Railway Company Board considered taking on women in the Swindon works. The idea was formerly rejected by management claiming a lack of toilet facilities. This was a common excuse used to keep women out of workplaces.

Despite the GWR policy, Fanny and Winnie Hyde are recorded as working there during World War I.

War disputes

Trade union leaders who opposed the war were quickly swept aside in the patriotic fervour of 1914. Industrial peace was declared as the country geared up for war production. Massive change led to rise in shop steward power and despite the war there were a number of disputes throughout the war.

In Bristol there were 51 stoppages from 1915-1918 including in the aircraft, boot and shoe industries. Tram workers struck in Bristol and Plymouth in 1917 and won a pay rise and union recognition. There were railway strikes in Newton Abbott, 1,000 workers walked out at the Co-op in Plymouth and workers at the furniture-makers, Shapland and Petter in Plymouth were involved in a long-running dispute.

Workers at Stoke Canon paper mill near Exeter lost their jobs and homes in a dispute. Asylum workers walked out in Bodmin and Exeter.

Women workers at the Exeter shirt collar factory took strike action over pay.

Women workers at the Exeter shirt collar factory took strike action over pay.

In October 1918 some 10,000 GWR workers down-tools and marched with brass bands at the front to Swindon Town Hall to protest at food prices and profiteering.

Refusing to kill

The conscientious objectors of the First World War laid the foundations of non-violent protest against war Following conscription in 1916 around 16,000 men registered as conscientious objectors. 4,500 were sent to do work such as farming, 7,000 were given non-combatant duties, but 6,000 were forced into the army and when they refused orders they were sent to prison. Often ridiculed and taunted, these objectors were often brave pacifists and protesters against the war.

A meeting of the Independent Labour Party Branch at Dartmoor during the war

Dartmoor Prison was re-opened to house more than 1,000 conscientious objectors and renamed ‘Princetown Work Centre’. The Bishop of Exeter refused the use of the church in the prison. Put to work in and out of the prison, the objectors cleared a rectangular patch on the moor surrounded by a seven-foot-high dry stone wall. It had no purpose and decades later was still known as ‘Conchies Field’.

Hubert Whiteford was the middle of three brothers from St George in Bristol. Graham, the eldest, enlisted, Wilfred the youngest joined the Non Combatant Corps. Hubert refused to fight on political grounds and was imprisoned in Wansworth. Their father was said to be proud of all three of his sons.

After the First World War, the No More War Movement was established to strive for revolutionary socialism but not to take part in any war.

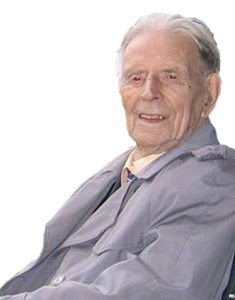

Harry Patch (1898-2009) was the last First World War veteran before he died at the age of 111. Harry left his Combe Down home in Somerset to become a reluctant soldier with the Duke of Cornwall’s Light infantry.

By the third battle of Ypres, Passchendale, Harry was a lance corporal and ‘went over the top’ as part of an offensive that cost some 70,000 lives. The horror that he witnessed traumatised him to such an extent that he could not talk about it until he turned 100-years-old. He recalled comforting a dying man ripped from shoulder to waist by shrapnel whose last word was “mother”. Harry and his comrades agreed to aim for the German legs to avoid killing them. In September 1917 he was badly wounded in the chest in an explosion that killed three of his mates. Harry came back to the West Country to recover during which time he met his first wife, Ada. After the war he became a plumber in Bath. He later accused politicians who led countries to war as “organising nothing better than legalised mass murder.”

As the old war veterans died, Harry became one of the diminishing few survivors who could recount first-hand experience of the trenches. With the help of Richard van Emden, he wrote his autobiography called The Last Fighting Tommy. Harry’s death in July 2009 and funeral at Wells Cathedral led to many tributes. Not even ceremonial weapons were allowed at the ceremony.