Bristol prospered from its port and international trade. The city was built around the river and workers, many highly skilled, organised together to settle grievances and press for better conditions. As early as 1746 there were disputes between sailors and the Merchant Venturers who ran the port. Some 2,000 sailors marched up Brandon Hill and agreed to stick together in a “solemn combination” until they were paid at least fifteen guineas. According to research by Steve Poole in his book A City built upon the Water: sailors accepted less would do so on ”pain of being immediately hung up on a gallows”.

In 1783 the Bristol sailors struck again over pay parity with other western ports. Disputes are recorded in 1784, 1794, 1800, 1815, 1826 and 1859. In 1792 the union organiser John Rhodes was blacklisted for his activities. John Gast, a union pioneer left Bristol for London in 1774. Gast helped organise the Hearts of Oak Benefit Society during a shipwrights’ strike in 1802 and was advocating workers’ rights in radical pamphlets. In 1822 Gast formed a Committee of the Useful Classes, a national trades council, and in 1824 he was the first secretary of the Thames Shipwrights union. Gast was a Chartist and a dissenting preacher.

In 1825 the Select Committee on the Combinations Laws that outlawed unions, described how Bristol carpenters were enforcing local labour and persuading strike breakers to return to Plymouth. A year later shipwrights were gaoled for forcing a striker to ‘ride the stang’. This involved parading the victim tied to a pole, covered in soot and forced to toast the union.

Coffin Ships

Greedy owners would sometimes overload ships to boost their profits but such ships were liable to capsize in rough seas. Some brave sailors took matters into their own hands and refused to board such ships even if this meant imprisonment.

In 1855, a group of sailors calling themselves ‘The seamen of Great Britain’ wrote to Queen Victoria complaining that courts had found them guilty of desertion for refusing to go to sea in dangerous ships. Around the same time, an inspector of prisons reported that nine out of twelve prisoners in the jails of South West England were sailors, imprisoned for twelve weeks for refusing to sail in so-called ‘coffin-ships’ they considered to be unseaworthy.

In 1860 a crew of twelve refused to take the Juno from Bristol to Quebec after the ship was taking in water. They were arrested and nine stood their ground and were sentenced to twenty-one days’ hard labour. Several crews were jailed in 1866, one after the other, when they refused to set sail in an old ship named Harkaway. The sailors complained that even at anchor on a calm sea, the ship took in water to a depth of more than a metre each day. The Harkaway finally set sail for the West Indies with its loaded cargo after it had taken on board its fifth crew.

In 1875 the Sunbeam put into Plymouth Sound with its crew refusing to cross the Atlantic due to the ship’s poor conditions. In court the sailors claimed that the ship was utterly rotten and that they preferred prison to an untimely death. Found not guilty of mutinous conduct the fifteen men were freed. In support, the Plymouth Co-operative Society gave them £5.

Samuel Plimsoll – Bristol champion for sailors

Born in Bristol in 1824, Samuel Plimsoll is remembered by unions for his services to those who work on the sea. As an MP his first speech helped legalise trade unions and he raised awareness of the hazards of methane gas in mines. His memory live on in the name of the line that all ships must paint on their hulls to prevent overloading. Plimsoll fought long for ship safety and the Merchant Shipping Act of 1876 made load lines compulsory. The basic symbol, of a circle with a horizontal line passing through its centre, is now recognised worldwide. When a ship is loaded, the water level must not go above the ‘Plimsoll Line’ with variants displayed to take into account temperature, saltiness, season and location.

Falmouth Packet strike

The Post Office Packet service ran out of Falmouth Port from 1688. Pay was poor but sailors were protected from ‘impressment’ into the navy and could supplement wages by taking unofficial cargo. At the end of 1809 the authorities decided to enforce the ban on private trade. The clampdown led crews to ask for more money but the Post Office refused. On 24th October 1810 customs officers boarded two ships: Prince Adolphus and Duke of Malborough and confiscated illicit goods. The sailors refused to take the ships to sea unless their goods were returned. Captain Bull read a notice of impressment and seized the protestors.

The next morning a massive crowd descended on the Packet’s office at Bell Court in Falmouth to demand the release of their fellow seamen. The Riot Act was read. Led by Richard Pascoe and John Parker, a mass meeting was called on the town’s bowling green. It demanded the release of the men and a pay rise. Another meeting was summoned at the Seven Stars Inn at Flushing. The navy sent marines to arrest the leaders but the community sided with the sailors and the men escaped. Naval support ships arrived from Plymouth to escort the Packet vessels out of Falmouth and fearing the loss of trade the protest subsided.

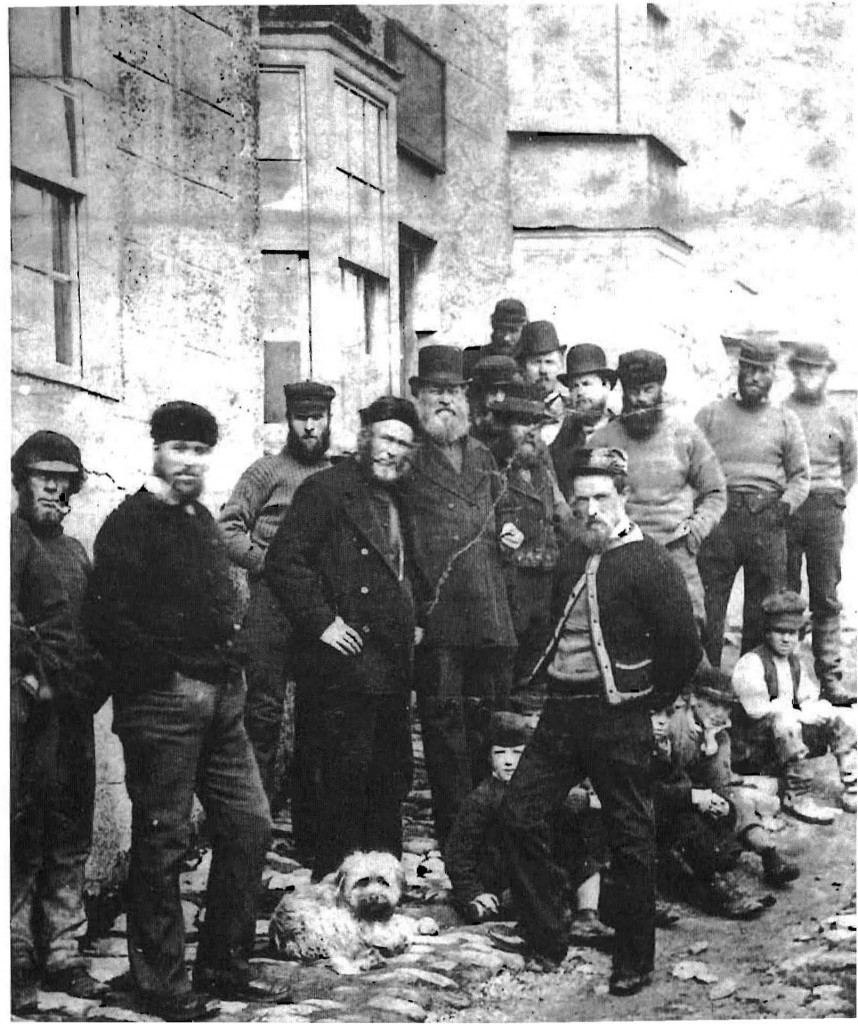

Pilots of Pill

Pilots of Pill

The treacherous waters of the Severn Estuary and the hazardous River Avon to Bristol Port demands careful navigation and skilled pilots. The small village of Pill near Avonmouth traditionally provided the pilots. The village had been notorious for smuggling. In 1577 four pirates were caught pillaging a small ship anchored at Pill. They were hanged by their feet from the bridge opposite Prince Street to be drowned by the incoming tide.

The Pill pilots were self-employed and competition was fierce but fair. The first pilot to catch sight and board an incoming ship would get the trade. The Bristol Society of Merchant Venturers regulated the pilots but they were an unruly community and fought hard to protect their interests.

The proud Pill community resented outside interference in the way they lived and worked. They kept the press gangs at bay and helped sailors escape capture. In 1825 the pilots fought pay cuts by stopping ships heading for Bristol and in 1836 between 25 and 50 Pill men attacked the crew of the steam-tug Fury that was touting for business at Portishead.

Steam power ended much of the work of the Pill crews but pilots were still needed even though Bristol was losing trade to other ports such as Liverpool. It was injustice that united the pilots. Edward Canby had his licence revoked for life after the grounding of the steamship Cornwell in the Avon under the suspension bridge. The pilots thought the punishment excessive and their protest won public support. Bristol Trades Council took up the case at its first meeting and eventually the authorities reconsidered. In 1880 an argument over the way pilot crews were picked caused a strike amongst westwardmen or boatmen. During the course of the dispute a ship was prevented from leaving the river by a chain. Eleven men were summoned to Bristol magistrates where they promised not to repeat any unlawful acts.

The pilots lost faith in the law to protect them and they established the Bristol Pilots’ Association, a trade union. In 1883 a meeting in Bristol agreed to establish the United Kingdom Pilots’ Association. Bristol pilot, Captain Henry Langdon became the first Secretary.

Read about the Plymouth-born mutiny here

Pilots of Pill

Pilots of Pill