The china clay industry was a major employer in Cornwall but employers fought to keep unions out. There were some local disputes such as the strike in 1872 by 200 clay workers at Thomas Stocker’s West of England Clay Works. They won big pay rises of 25-50 per cent but by 1875 a trade slump led employers to try to cut wages.

A strike at the Martyn’s clay works began on 2nd July. The workers marched from pit to pit gathering support. A mass meeting in St Austell heard strike leader Joseph Matthews appeal for a disciplined, peaceful dispute.

Some employers backed down but when a strike deputation met the clay merchants they warned the workers that they had large stock piles and would win the dispute. When the strike held firm, the employers gave in and restored pay levels.

After this success, Matthews set up the St Austell China Clay, China Stone and Surface Labourers’ Friendly Union. Even with ‘Friendly’ in its title the Cornish bosses were determined to kill off this union before it took hold. Matthews and other activists were sacked.

A strike was called and some 2,000 workers came out. The dispute quickly turned nasty with clay captains threatening workers and reports of violence against strike breakers. 150 police were called in from Plymouth. Early morning raids saw union leaders: Rundle and Hawkey arrested for intimidation. They were gaoled for six weeks and fined £50. Matthews was also caught and given ten weeks’ hard labour.

The strike dragged on through Christmas and with no money coming in workers were forced back to work on 22nd January. Northern unions were reluctant to give cash support as Cornish miners had a reputation as strike breakers.

In the early 1900s the new Workers’ Union started organising clay workers. Joe Harris, Matt Giles and Charles Vincent led the campaign.

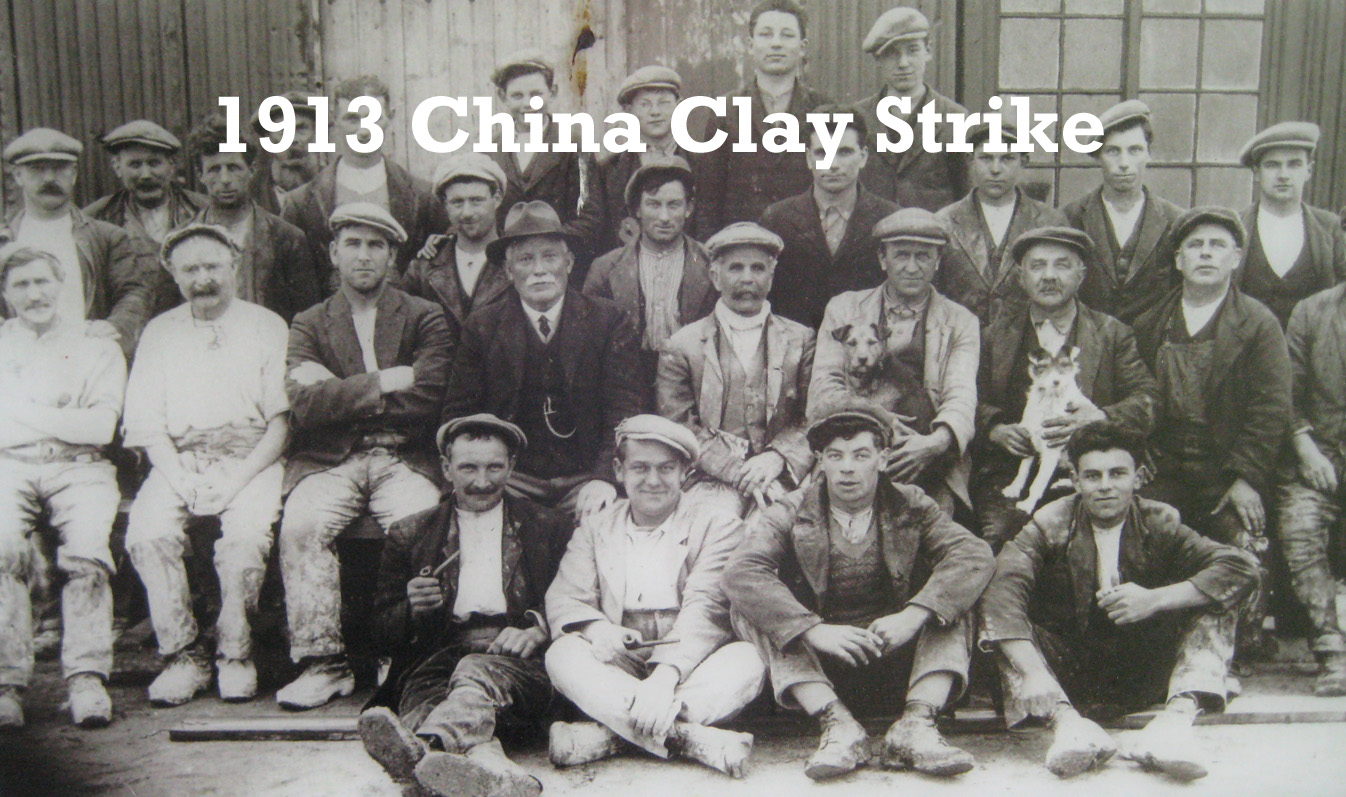

1913 Clay Strike

1913 Clay Strike

In 1911 they pressed for improvements in their harsh conditions. Their demands were:

- An eight-hour-day

- Wages paid once a fortnight

- An hour a day lunch-break

- A rise of five shillings to £1.25s a week

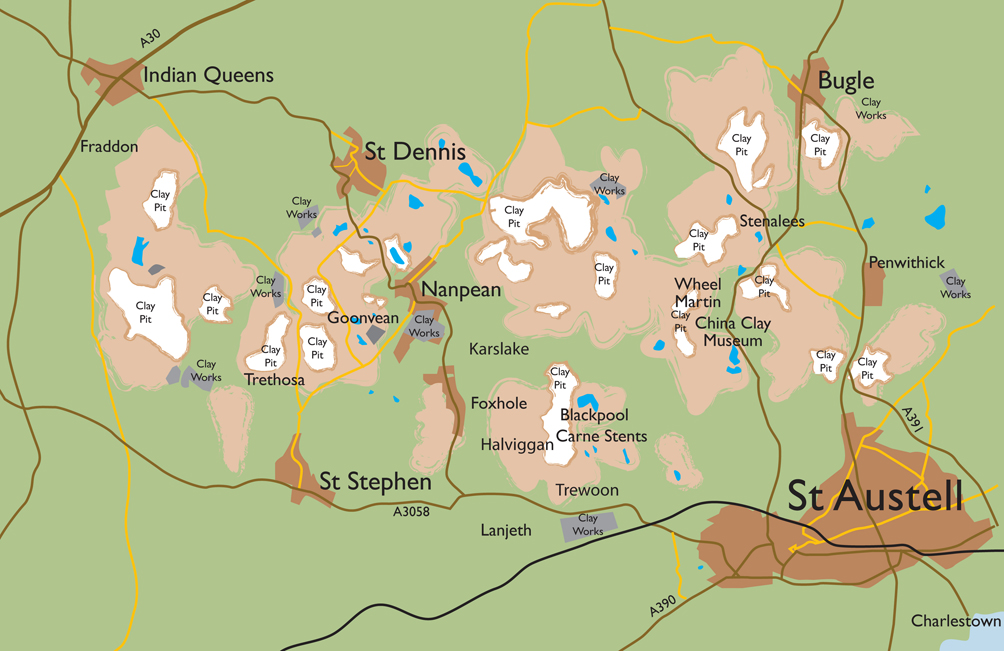

The clay companies rejected the demands and on 21st July 1913 the workers at the Carne Stents Pit near Trewoon walked out. The dispute quickly won the support of almost all clay miners. Julia Varley, an organiser from the Black Country came down to rally clay wives.

A few strike-breakers were reportedly beaten up and at Nanpean a can of dynamite exploded on the window sill of a shift manager’s house.

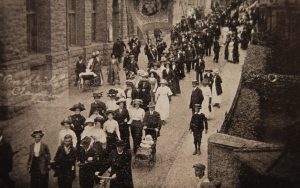

On 2nd August a procession through St Austell was led by the Rev H Booth-Coventry and Matt Giles. A meeting of some 2,000 miners held at Bugle in August 1913 was warned by the Deputy Chief Constable. “I don’t want you to get into trouble,” he declared. The workers marched on the engine house in Karslake. They made their protest and walked back singing hymns.

On 2nd August a procession through St Austell was led by the Rev H Booth-Coventry and Matt Giles. A meeting of some 2,000 miners held at Bugle in August 1913 was warned by the Deputy Chief Constable. “I don’t want you to get into trouble,” he declared. The workers marched on the engine house in Karslake. They made their protest and walked back singing hymns.

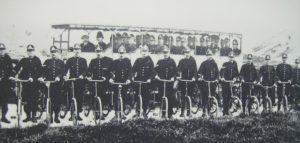

The 200-strong police force realised they were out-numbered. 100 Welsh police from Glamorgan were brought in along with 60 from Bristol and 30 from Devon. Some had been trained to break up strikes and were considered less likely to be swayed by the local community.

As the strike dragged on the miners ran out of money. They sold what they could, including family treasures, to survive.

As the strike dragged on the miners ran out of money. They sold what they could, including family treasures, to survive.

In October the Glamorgan police seemed set on a fight at Bugle. Julia Varley, was pushed to the ground, batons were drawn and when the police charged some of the miners were wounded.

In a poll of the workers 2,258 voted to continue the strike but the strain was being felt. Pickets attacked Halviggan engine house and teenager, Howard Vincent shot PC Collet, a local police officer, in the thigh.

On 5th October a conference in the Public Rooms in St Austell voted to return to work.

The china clay Workers Union Branch Committee open the new union hall in Nanpean

Despite the defeat spirits were remarkably high and the strike helped bolster trade unionism across Cornwall.

With nowhere big enough for members to meet, on 1st January 1914 a Union Hall was opened by Joe Harris in Nanpean, built for £100. A few months later another hall was built at Foxhole. It was opened by Rev Booth-Coventry. By 1933 the wooden hut was replaced and became the offices for the Transport and General Workers Union.

Joe Harris became a popular Labour leader in Cornwall and union membership grew. In February 1914 there was a new three-year pay deal that actually gave more than the 25 shillings claimed in the strike.

The dispute politicised the workforce. When war broke out many clay workers refused to volunteer to fight. The strike hero, Rev Booth-Coventry was even booed when he appealed for the workers to support the war effort.

Thanks to the China Clay History Society.

Stocker’s Copper

A TV Play for Today called Stocker’s Copper was shown in 1972 telling the story of the strike. Written by Tom Clarke, the play focuses upon the relationship between clay striker and police officer.

In the film, Manuel Stocker, one of the striking miners, is forced to earn cash by taking in a lodger, Herbert Griffith, a police officer from Glamorgan. Their friendship starts to grow but the tension of the strike increases. The film ends as the police read the Riot Act and break up the picket-line to smash the strike and the relationship between the two men.

1913 Clay Strike

1913 Clay Strike