The plight of the unemployed has always been a central issue for the labour movement. During the 1920s and 1930s, how to represent the unemployed roused fierce debates within unions and the Labour Party and ultimately split the minority Labour Government.

The plight of the unemployed has always been a central issue for the labour movement. During the 1920s and 1930s, how to represent the unemployed roused fierce debates within unions and the Labour Party and ultimately split the minority Labour Government.

The TUC tried to get trades councils to support the unemployed and in 1921 the Bristol Unemployed Association was organised by Teddy Parker, Secretary of Bristol Trades Council.

The National Unemployed Workers’ Movement was set up in 1921 to draw attention to the plight of unemployed workers and to fight the Means Test – where workers had to prove their hardship. It organised the unemployed on a national basis and the central element of its activities was a series of hunger marches.

The first national hunger march in 1922 generated media scare stories that it was a ‘Red Plot’ funded from ‘Bolshevik gold’. The march was supported by the TUC and joint activities were organised such as ‘Unemployed Sunday’ a national protest on 7th January 1923.

In September 1923 the TUC met in Plymouth and endorsed statements of joint work with the NUWM. Another national demonstration was held and the TUC held a special Congress on unemployment. In 1927 unemployed South Wales miners marched to London. On 9th November they entered Bristol with every marcher wearing a miner’s lamp. The miners joined the Bath Remembrance Parade before moving on through Chippenham to Swindon. They were met by AJ Cook and Labour leaders from Swindon. Wal Hannington, leader of the NUWM, said: “Thousands of Swindon workers gathered in the streets. Railwaymen in working clothes, carrying red flags, marched at the head of the army. Crowds lined the streets with tear-dimmed eyes as the marchers passed.” They were fed and put up in the public baths where a great meeting was held. 3,000 filled the hall with many more unable to get in.

The government was under pressure to cut spending and a committee including Margaret Bondfield from the TUC General Council recommended cuts in benefit levels. This brought protests across the labour movement. The suggested reduction to 8s led Bondfield to be nicknamed ‘eight-bob-a-week Maggie’.

The NUWM was seen by many as a Communist Party front and its attacks on the TUC led to bitter divisions. By the time the second national hunger march was organised in January 1929 tensions were growing between the NUWM, the TUC and the Labour Party. A contingent left Plymouth on 8th February.

The NUWM was seen by many as a Communist Party front and its attacks on the TUC led to bitter divisions. By the time the second national hunger march was organised in January 1929 tensions were growing between the NUWM, the TUC and the Labour Party. A contingent left Plymouth on 8th February.

In May 1929 Labour formed a minority government with registered unemployment at over 2.5 million and rising. The NUWM march in 1930 set off despite opposition from Labour and TUC leaders.

The decision to cut unemployment benefit split the cabinet and in 1931 Ramsay MacDonald joined with the Tories and Liberals to form a new National Government.

In September 1931 the NUWM organised a march to the TUC Congress in Clifton, Bristol. It led to serious clashes with the police and many local workers turned out to support the protest.

In 1932 the NUWM organised more marches across the country including a number in Bristol. ‘Struggle or Starve’ was the theme.

Power not Pancakes

On Shrove Tuesday 1932 the police charged the march in Old Market Street, Bristol and two weeks later there was an even larger confrontation. The marches and pickets on the Poor Law Administrators led to the postponement of the benefit cuts. But the NUWM’s rise was short-lived. The leaders were arrested and by 1933 the Bristol branch was all but finished. Another march left the West Country in 1934.

Peoples March for Jobs

Peoples March for Jobs

Under the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher, unemployment across the country rose sharply. The South West was not immune and many jobs were shed as companies closed down or laid-off workers.

By 1983 there were around 250,000 people out of work, including a quarter of all those under 25 years old. The TUC supported a People’s March for Jobs that set off from Land’s End towards London on 11th May. Twenty unemployed marchers were selected to represent the South West.

By 1983 there were around 250,000 people out of work, including a quarter of all those under 25 years old. The TUC supported a People’s March for Jobs that set off from Land’s End towards London on 11th May. Twenty unemployed marchers were selected to represent the South West.

As they marched through the region they generated press coverage that helped highlight the plight of those looking for work.

In Gloucestershire, trade unionists led an initiative called Gloucestershire Campaign for Jobs and Recovery. It brought together a range of partners and concerned individuals to organise against unemployment and to develop ideas to develop the local economy. A large meeting of unemployed people was held in Gloucester Cathedral and protest marches were held against cuts in public services.

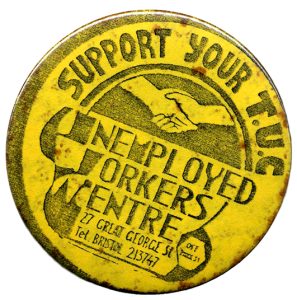

TUC unemployed workers’ centres were established across the South West to provide advice and support.

Tramping to Internet

Tramping to Internet

When craft printers found themselves without work some would ‘tramp’ from town to town in search of employment. The system was encouraged by the early union societies to relieve unemployment and prevent employers from cutting pay.

A ‘Tramping Relief’ system was developed under which members could report to the local secretary. A Relief Map gave mileage allowances to be paid and overnight expenses. Advice would be given on available work and those vacancies to avoid if the employer refused to pay the rate or recognise the Society. So effective was the system that non-society workers would try to forge cards. This led, in 1830, to the formation of the first national union to oversee the scheme.

This tradition was maintained through the payment of Unemployment Benefit and job search assistance.

Co-operative training

In the 1990s printing faced technological changes and cut backs. In Gloucestershire unemployed print workers formed a unique co-operative training and employment service. Members could learn the very latest technology, get news on vacancies and help with CVs and job applications. The Graphical Employment and Training Group was very successful, helping hundreds back into work.

Peoples March for Jobs

Peoples March for Jobs Tramping to Internet

Tramping to Internet