In May 1926 workers across Britain stopped work in support of the miners who faced cuts in pay and longer hours. The strike ended in defeat and division but it was a week when working people came together in strength and solidarity.

In May 1926 workers across Britain stopped work in support of the miners who faced cuts in pay and longer hours. The strike ended in defeat and division but it was a week when working people came together in strength and solidarity.

The dispute had been brewing for some time and when it came it set trade unions against the Conservative Government led by Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin. Chancellor, Winston Churchill, took charge of the government’s propaganda including acting as a zealous editor of the British Gazette. He sought to portray the strike as a revolutionary act that aimed to bring down democracy and impose communist rule. The TUC produced its own newspaper: The British Worker.

Despite strong support for the stoppage, fearing trade union divisions, the TUC called off the strike after nine days leaving the miners to fight on alone for another seven months. The defeat left trade unions badly weakened.

Bristol

On the first day of the strike 18,000 Bristol workers downed tools. Nine days later, just before the strike was called off, that number had doubled. Power station workers, builders, printers and engineers went on strike although the trams and local press managed to continue operations.

Warships were moved into Avonmouth and City docks and sailors guarded the power station. A General Strike Committee was established by the Trades Council and special sub-committees were formed to deal with communications and publicity. A system of cyclist messengers carried information to all points of the city.

Devon

In Exeter some 3,500 workers answered the strike call. Railways came to a halt and only truncated editions of local newspapers appeared. The Devon County Show was postponed but buses continued to run.

When the strike was called off, Newton Abbot railway workers refused to return to work until local trade union and Labour Party activist, Mr WG Chinn was re-instated. Workers marched through the town with banners “We Want Chinn” and they stayed out until the company gave way.

When the strike was called off, Newton Abbot railway workers refused to return to work until local trade union and Labour Party activist, Mr WG Chinn was re-instated. Workers marched through the town with banners “We Want Chinn” and they stayed out until the company gave way.

Exeter Trades Council continued business as usual during and after the strike. The first item of business of the meeting held on 10th May was not the progress of the strike but a letter from the town clerk on the long-running issue of street traders.

There were battles with police in Plymouth on Saturday 8th May when tram workers tried to stop a small number of blacklegs. A different sort of contest took place on the same day with a football match at Plymouth Home Park between strikers and the police – the strikers won 2-1.

Strikers and police at the General Strike football match

Gloucestershire

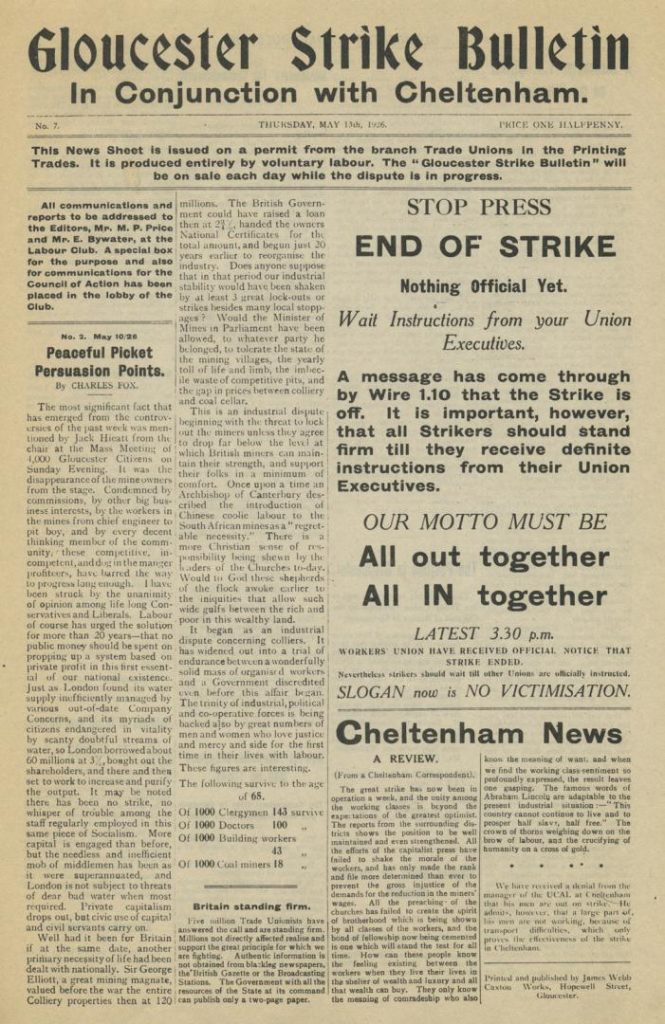

The presses of the newly formed co-operative printers were made available to volunteers from the Typographical Association to produce a daily newspaper. The Gloucester Strike Bulletin is a rare example of such a publication and gives a fascinating insight into the strike from the union side. Such publications were discouraged by the TUC who wished all communications to go through the official British Worker.

In the first edition of the Gloucester Strike Bulletin, local workers are congratulated for “their fine stand against the tyranny of low wages and long hours down the mines.” The case was made for the nationalisation of the coal industry.

In the first edition of the Gloucester Strike Bulletin, local workers are congratulated for “their fine stand against the tyranny of low wages and long hours down the mines.” The case was made for the nationalisation of the coal industry.

As the strike developed, the Bulletin reported on growing support around the region. The docks came to a standstill and the unions issued permits to let essential foodstuffs pass. Electricity was cut to allow hospitals and homes to have power but not industry. Railway workers were almost all out as were engineers, wood workers, printers and builders. Postal workers said that “they were serving the workers best at the moment by remaining at their posts.”

The third edition had become “In conjunction with Cheltenham” where the Trades Council had formed a Council of Action, backed by 2,000 organised workers.

On the railways the reports were: “Lydney, Cinderford, Newnham, Exeter, Taunton, Totnes, Penzance and Bristol all out except a few clerks at Exeter.”

A mass meeting at the Skating Rink, India Road, Gloucester received a rousing speech from Albert Purcell, the MP for the Forest of Dean. Gloucester Trades Council and Labour Party Chairman Jack Hieatt gave a “fine fighting speech.” He described how he had just returned from “a gigantic mass meeting in Swindon, he said that never in his life had he seen anything to equal the spirit of solidarity which had been displayed there.”

Ralph Anstis in his book Blood on Coal, describes the strike in the Forest of Dean: “The effects of the rail strike were soon noticeable. At Awre station milk churns were left uncollected and Symonds Yat, Upper Lydbrook, Coleford, Parkend, Whitecroft, Bullo Pill and Blakeney stations were closed with the staff out in support of the miners. In Lydney six hundred tinplate workers ceased work.”

On Sunday 9th May the North Street Picture House in Cheltenham was filled to capacity to hear strike reports ending with the Cheltenham Labour Male Voice Choir render some “rousing glees in a splendid manner”. Stroud was reported to have held “Fine meetings,” with “Position satisfactory and orderly.” Cheltenham had only two trams running and in Tewkesbury the strike was still going strong. The Bulletin reported on the Strike Fund, football matches between the areas, concerts, a call for pickets to guard the allotments of trade unionists for fear of looting and other national news.

The seventh and final edition first appears with the headline “END OF STRIKE” and “Our motto must be all out together, all in together”. But by the end of the day a second version was quickly produced saying “STRIKE STILL ON. Employers want you to crawl back on their conditions. Show them what you think by staying out.”

Unions fought against victimisation as the strike collapsed and discipline was maintained. The all-male Typographical Association, stayed on strike when one employer refused to take back women bindery-hands. All were allowed back to work.

Somerset

At the start of the dispute a mass meeting was held in the YMCA Hall, Taunton. With 400 packed inside around a similar number unable to get in, the meeting heard from Jas Young for the railway workers. A joint strike committee was formed. The following day the strike was on, bringing to a halt the railways, the movement of coal, livestock, bricks and tiles.

By the third day of the strike about 1,000 brick and tile workers walked out, prompted by the sacking of strikers, although some confusion remained over the scale of the stoppage in the building trade. A mass meeting held at Jarvis’s Field in Taunton received a report on the situation in Bridgwater from Jimmy Boltz of the T&G. About 1,000 workers joined the strike at Highbridge especially from the large locomotive works. There was a report of a consignment of cheese needing to use a cross-channel steamer to get from Highbridge to Weston.

Swindon

Between 5,000 and 6,000 people gathered in Swindon Park to hear telegrams read out from all the unions calling on members to stop work. Jack Hieatt, T&G and Gloucester Trades Council Chairman spoke in solidarity along with Councillor WH Robins of the Railway Clerks.

Support for the strike held firm. On 10th May the Swindon Engineers met in the Mechanics Institute. The minutes record that “All members of the DC present. It was one of the finest meetings ever held, the hall being packed to excess and the members very enthusiastic.”

The next day, when the strike was called off they assumed they had won and were shocked to learn of the terms. Another mass meeting in the park resolved not to resume work without a guarantee that all strikers would be re-instated. Employers tried to impose conditions for re-engagement and so the strike continued. On 13th May there was a riot when the Mayor ordered the trams to start running. Two left the depot for Old Town and Rodbourne. At the town centre thousands met them. Women were reported as having aprons full of stones. Fearful of the consequences, the Mayor ordered the trams back to the depot. Two days later a settlement was reached for a full return to work.

The legacy of the Strike

The TUC General Council concluded that a settlement was out of reach and an end to the strike had to be found. Some unions faced bankruptcy and although the resolve of many strikers remained strong many workers feared losing their jobs.

The failure of the General Strike was a disaster for trade unionism and working people. The government used the outcome to introduce savage new anti-union legislation. The Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act of 1927 outlawed sympathy strikes and confined strikes to the trade or industry involved. It opened up unions to civil damages and limited the right to picket. It attacked the political use of union funds and banned civil servants from joining unions with political objects. Membership slumped to below five million for the first time since 1916. Union funds were drained by the dispute leaving them ill-equipped to fight back. Unemployment soared and employers took advantage of union weakness.

Trade unionism did not recover until after the Second World War when the Labour Government relaxed the laws.

See more: