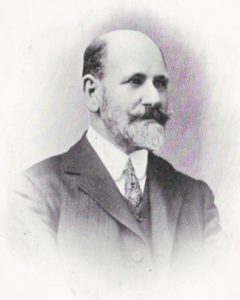

Sam Whitehouse, Somerset Miners’ Agent

The Somerset Miners Association was formed in 1872. In 1988 Sam Whitehouse was the first Agent and Secretary with around 2,000 members. After a strike in 1889 the local unions joined the Miners Federation of Great Britain and Whitehouse joined its executive.

The Somerset Miners Association was formed in 1872. In 1988 Sam Whitehouse was the first Agent and Secretary with around 2,000 members. After a strike in 1889 the local unions joined the Miners Federation of Great Britain and Whitehouse joined its executive.

They demanded a living wage and in response the employers locked them out in 1893. It ended with what became known as the Rosebery Settlement that established a national minimum wage for mining. The Association promoted labour representation on various public bodies in the area. Whitehouse was a member of the Governing Board of the Royal United Hospital, Bath. The miners also took a keen interest in technical instruction for miners, provided by the County Council through a special committee, of which Mr. Whitehouse was Secretary.

During this period various national Labour leaders came to the Somerset coal area including George Lansbury, Kier Hardie and Arthur Henderson. On 20th August 1915 the Radstock and District Labour Representation Committee was formed to get candidates elected on all local and national bodies. In 1917 the Radstock Independent Labour Party complained at being barred from Victoria Hall due to the war.

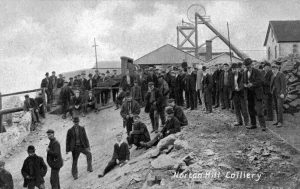

Norton Colliery, Somerset c 1908

On 16th January 1918 inaugural meeting of the Radstock Trades and Labour Council was held at the Miners’ Office.

Policing the 1921 strike at Lodlows Colliery, Radstock

During the 1921 strike he miners stayed out for some three months.

After 1945 the Somerset Association became the West Coutry Area of the National Union of Mineworkers. As the pits closed it was absorbed into the South Wales area.

Somset mining ended in 1973.

See Somerset Miners history on Union Ancestors.

Bristol and Kingswood miners

Coal was dug in around Bristol from the sixteenth century and in the 1800s there were pits in Bedminster, Easton, Kingswood and Parkfield. Kingswood miners were often at the forefront of campaigns over living conditions. A strike in 1865 saw some 150 miners win against Brain and Company.

In 1874 the Gloucestershire Miners’ Annual Gala Day was held at Rodway Hill, Mangotsfield and addressed by a South Wales miner. 4,000 Bristol miners went on strike in June of that year. An appeal notice explained they were “struggling for what we consider is nothing but just and right. We consider that out wages are just enough to live from hand to mouth and seeing the danger we are exposed to and the risk of life and limb . . . we are entitled to a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work”. On 18th July the miners accepted arbitration to settle the dispute.

In April 1890 the Agent for the Bristol Miners’ Association, Mr W Whitefield, wrote to all 3,000 members suggesting that they pay 3d a quarter to send three or four Labour MPs to Parliament. By 1906 the miners joined the Labour Representation Committee.

1911 Strike

In 1911 the miners in Bristol, some 2,000 men, went on strike in support of their claim for an extra 3d per day; the same increase recently awarded to the Somerset miners. The strike ended after three months when the miners accepted a compromise. Although the men marched to meetings whilst the strike was on, there was no trouble and after they resumed work their agent received a letter from the Chief Constable expressing his appreciation of the way the strike had been conducted. The Easton pit closed at the end of the strike.

By March 2012 the Bristol miners were on strike again as part of a national dispute. Strike pay amounting to 10/-per week plus 1/- for each child of married men was paid initially but a couple of weeks later the amount had to be reduced to 7/6. The strike caused disruption to local industry with rail services drastically curtailed and many workers put on short time; the Bitton Paper Mill had to close. The Salvation Army provided breakfasts for children in Bedminster, feeding more than 600 each day; meals were also being supplied at the Mission Hall in New Street, St. Jude’s, and at the Grafton Street Hall, St. Philip’s, where over 400 children were being fed. Out of work miners and shoemakers hewed coal from the base of two old quarries in a field off Charlton Road, Kingswood. A young man called William Burford died when searching for coal in a hole at Trooper’s Hill, St. George; the roof fell in and buried him.

See more: