As news of the sentence spread, the fledgling trade union movement began to organise a campaign for their release. On 24th March 1834, there was a Grand Meeting of the Working Classes, called by the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union on the instigation of Robert Owen. The meeting was attended by over 10,000 people: it was just the beginning. The agitation spread and grew. The London Central Dorchester Committee was formed to campaign for the men’s pardon.

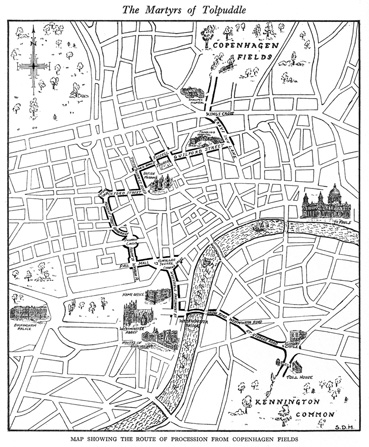

A vast demonstration took place on 21st April 1834. Up to 100,000 people assembled in Copenhagen Fields near King’s Cross. Fearing disorder, the Government took extraordinary precautions. Lifeguards, the Household Cavalry, detachments of Lancers, two troops of Dragoons, eight battalions of infantry and 29 pieces of ordnance or cannon were mustered. More than 5,000 special constables were sworn in. The city looked like an armed camp.

A vast demonstration took place on 21st April 1834. Up to 100,000 people assembled in Copenhagen Fields near King’s Cross. Fearing disorder, the Government took extraordinary precautions. Lifeguards, the Household Cavalry, detachments of Lancers, two troops of Dragoons, eight battalions of infantry and 29 pieces of ordnance or cannon were mustered. More than 5,000 special constables were sworn in. The city looked like an armed camp.

By 7am the protesters began to gather marshalled by trade union stewards on horseback. Robert Owen, the leader of the Grand Consolidated Union and the father of the Co-operative Movement arrived.

The grand procession with banners flying marched to Parliament in strict discipline. Loud cheers came from spectators lining the streets and crowding the roof tops. At Whitehall the petition, borne on the shoulders of twelve unionists, was taken to the office of the Home Secretary, Lord Melbourne. He hid behind his curtains and refused to accept the massive petition.

The Government tried to resist the mounting protest but the agitation for the men’s release was maintained. William Cobbett, Joseph Hume, Thomas Wakeley and other MPs kept the question constantly before Parliament. Petitions came from all over the country with over 800,000 signatures.

By June 1835, ten months after the Martyrs’ arrival in penal colonies, conditional pardons had been granted by Lord John Russell, the Home Secretary.

Russell had jumped the gun: legally, a convict could not be conditionally pardoned under four years. The flurry of correspondence between Whitehall and the Sydney and Hobart Government Houses caused confusion and delay.

Thomas Wakley’s campaign continued. He presented 16 petitions to Parliament. There was nationwide agitation. Conditional pardons were not good enough.

The Tolpuddle men refused to accept compromises and after further pressure, the Government agreed on 14th March 1836 that all the men should have a full and free pardon.

Trade unions had won and survived their first big challenge. The six farm workers from Tolpuddle were on their way home as free men.

See also: Islington Remembers.