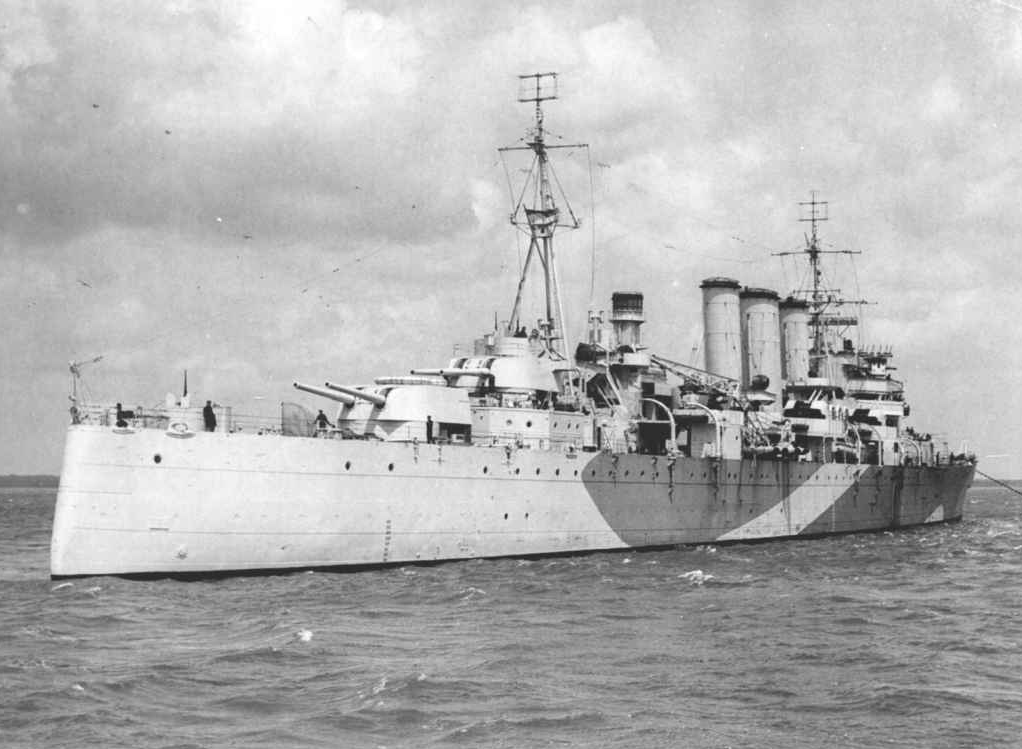

HMS Norfolk

There were strikes in Plymouth port in January 1931 when both watches on HMS Lucia refused orders after being denied Sunday leave. This was a time of heightened trade union activity and political discussion on and off the ships. The Rodney, the Adventure, the Norfolk and the Hood left Devonport on 7th September 1931. The usual waving crowds of wives and children had gathered on Plymouth Hoe and at Rusty Anchor. But the mood at home was one of anxiety as the men were facing the threat of drastic pay cuts. Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government had agreed a pay cut that would reduce wages to 1925 levels – for the ‘lower decks’ that meant one shilling taken from their four shillings a day. On 11th September, the ships were berthed at Invergordon on the Cromarty Firth in Scotland. The pay cuts were front-page news. A meeting of 600 sailors voted unanimously to strike.

Len Wincott

24-year-old Len Wincott who sailed from Plymouth emerged as one of the leaders. He was an Able Seaman on the Norfolk. The Admiralty’s attempts at conciliation failed to impress the agitated crews. On 15th September the crew of the battleship Rodney refused orders. Ten ships were affected by the mutiny. As each ship’s company stopped work they gathered on deck and cheered – passing the message down the line. Sailors used a system of whistles as signals for the action. As a consequence whistling on board navy ships is banned.

Many of the sailors sang the Red Flag as the mutiny spread. Even the marines backed the striking seamen. It was an unprecedented show of defiance and solidarity, half the Atlantic fleet – some 12,000 seamen – mutinied. The rebellion excited headlines around the world. The pound plummeted on foreign exchanges. Within 24 hours the Admiralty capitulated and agreed to restore part of the wage cut. The ships were ordered to return home.

The government said it wanted no reprisals but Len Wincott and 396 ratings were discharged from the service. In 1932, the Atlantic Fleet was renamed the Home Fleet, to purge the memory of the mutiny. Len Wincott’s involvement in the mutiny would shape a life full of contradictions. He worked in the Soviet Union in a factory, as a translator, an actor, and was drafted into the Red Army during the Second World War where he survived the siege of Leningrad. After the war, he appeared in Soviet films, ironically, playing the classical Englishman. But he fell foul of Stalin’s Soviet regime, and he was accused of spying for the British. He spent nearly twelve years in a labour camp from 1944.

The one-time mutineer was invited to the British embassy in Moscow each year to celebrate the Queen’s birthday. Wincott returned to Plymouth for the launch of his book, the Invergordon Mutineer. He died in the Soviet Union in 1983. His ashes were scattered over Plymouth Sound from a Royal Naval tender. In the end, the navy afforded him every respect.