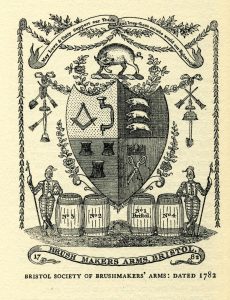

There are limited records of early unions but even the scant evidence shows they existed across the West Country through the eighteenth century. There was a union of Devon and Somerset wood workers as early as 1717. The National Society of Brushmakers can be traced back to 1747 with a Bristol branch in 1782. Its democracy involved a tin box. The secretary would write out the question and put it in the Tin Box. It would be passed around in secret for the members’ ‘voices’ and any shop holding the box for more than four hours would be fined. It could take a week to go around before the outcome was declared at the next meeting.

In 1792 a large body of colliers assembled near Bristol in to demand a rise of 2s per week. They were apparently encouraged by the success of shoe makers and other tradesmen. The miners went to Kingswood to get others to “concur in the same unlawful combination”. Some 2,000 colliers marched through Bristol on their way to the pits in Bedminster, Ashton and Nailsea.

In 1800 the Combination Acts that made unions illegal failed to stop growing movement. A Parliamentary report found: “That the laws have not only not been efficient to prevent combinations of masters or workmen, but on the contrary have, in the opinion of many of both parties, had a tendency to produce mutual irritation and distrust, and to give a violent character to the combinations, and to render them highly dangerous to the peace of the community.”

Thomas Helliker, Trowbridge shearman apprentice

The Wiltshire Shearmens’ strike of 1802 led to the hanging of an apprentice Thomas Helliker. The shearmans’ union was in breach of the Combination laws but it was well organised and the strike brought the Wiltshire mills to a stand-still. During the stoppage a mill was burned down and Helliker was blamed, even though there was no real evidence against him. He was hanged in Salisbury the day before his nineteenth birthday. Read more about the West Country cloth battles here.

When the combination laws were repealed in 1824 unions began organising openly. Strikes became more frequent. Employers panicked at the rise of unions but the government feared that re-enacting the old Combination Laws would be too dangerous. Amendments were passed in 1825 to make life harder for unions but still they grew. In 1833 there were several significant strikes and the Home Secretary was lobbied to re-enact the Combination Acts.

The Grand Union

The General Trades’ Union was established as a big union for all workers and on 7th September 1833 The Pioneer, its magazine was published. A few months later the organisation became the Grand Consolidated National Trades Union. It grew rapidly with estimates of membership at around half a million. Reports showed that some 200 glove workers had formed a union and the radical Yeovil Political Union, established in 1831, was blamed for agitating the workers.

Workers would take an oath of allegiance and secrecy when joining the union. This was critical at a time when employers would victimise union members. The rituals included swearing on the Bible and rites similar to those used in masonic practices. Wiltshire cloth workers took an oath when joining the union.

In January 1834 the Western Flying Post reported “considerable anxiety of the establishment of a trade union amongst the operatives.” The newspaper went on to state that: “We sincerely hope . . . that every attempt of wicked and designing men to sow discord between them will be strenuously resisted.” The most notable example was in the Dorset village Tolpuddle where farm workers formed a Society to defend themselves against further pay cuts.

The victorious campaign to free the six ‘Tolpuddle Martyrs’ confirmed the basic right of workers to form independent unions.